For centuries, wells have been fundamental elements in Venetians' everyday life. Their increasing numbers can be explained with the always compelling need of supply and catch of fresh water; indeed through centuries their numbers grew up to six thousand.

As the poet Marin Sanudo (1466-1536) wrote "Venice lays in water without water".

Beaches were the only areas around Venice with fresh water.

Catchment basin architectural engineering is very likely to be developed through these natural wells' discovery, shaping with the collection of rainwater that was filtered and cleaned from sand.

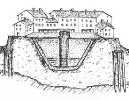

Rainwater was carried from roofs or from specific platform to deep wells dug in the ground, then filtered from many layers of sand, it remained pure and fresh. A bottleneck blanket of clay surrounded the well keeping it waterproof from brackish water.

The correct building of wells was very important and given to a very close guild called "Pozzeri", linked to the Bricklayers' Craft. All the members handed down from one generation to another and were obliged to work exclusively just for Venice wells.

However, rainwater was not enough to satisfy the city’s demand. Therefore, a new profession arise: the acquaroli. Their task was to fill Venetian wells with the water from the Brenta river.

However, rainwater was not enough to satisfy the city’s demand. Therefore, a new profession arise: the acquaroli. Their task was to fill Venetian wells with the water from the Brenta river.

Between 1609 and 1611 a little canal 13.5 km long and one meter wide was built, called La Seriola, it channeled a small part of the Brenta river water to Maranzani. In the intersection between Brenta river and the Seriola there was a marble inscription HINC POTUS URBIS (from here there is the drinking water for the city).

The acquaroli were divided in guilds but there were also the unauthorized ones, who piloted their boats called “forastiere” and could only retail water. These boats were also called “scoazzere” (“containing garbage”), since they were assigned to urban solid garbage transportation and so it was required to carry water on specific vats. This illegal job was basically well tolerated by the guild in exchange for a “contribution” of 20 coins per year.

With the need for the wells to be always peachy, above all from the health point of view, the Republic assured always a constant supervision. Besides infantrymen of the Waters’ Directors, Health and Municipality, were to control wells also priests and all the Leaders of the guilds, who shielded the keys of the tanks, which were opened twice a day: in the morning and in the evening after the toll of the “wells’ bell”.

Many wells were also in the church cloisters for the religious communities, which in some cases were obliged from the Republic to extend the use of the wells to the population during specific timings.

The basement of the wells stands above the so-called puteals.

This is a typical Venetian term and it refers to the stony building above the well cane that protects the breach. At the beginning, it was a very simple element just with security purpose, then with time passing by it became a rich and picturesque decoration in all the squares and courtyards.

Regarding the materials used for the construction of wells, builders begin to use materials from the ruins from Altino, Jesolo and Concordia. Capitals and column trunks were recycle, so the most ancient puteals are nothing more than sections of capitals, columns or funeral urns.

In the following centuries the so-called Istrian stone was unquestionably the most used material, thanks to its extraordinary resistance to salt and ease of transport by sea to Venice.

The Veronese limestones were also very common for their chromatic contrasts.

Over the centuries puteals, whose architectural word is puteale, acquired forms of art more and more elaborate and complex. The relief decoration was very vary and creative: plants, garland of fruits and flowers, curly leaves, little angels, shielded angels, peacocks, lion heads, allegorical motifs, ethical enrollments.

Palace internal courtyards had often a private well. It was like a certificate of merit for the wealthy families to build a public well for people.

That is the reason why on some pluteals you can find aristocratic crests and memorial writings as a sign of gratitude and reminder of the patrician family who commissioned it.

There are just two signed puteals: the bronze puteals of the yard inside the Doge’s Palace, dated to the 16th century, one of Alfonso Alberghetti, the other of Nicolò de’ Conti. We can add the one in Ca’ D’Oro realized in 1427 from a 20-year-old Bartolomeo Bon.

For all the other puteals, we can only make assumptions.

Telling the truth the Venetian well curb is often a standard product, packaged on the base of some prototypes with stylistic and artistic modifications that can be or not significant. As a confirmation, we have documented sources from 1424, when the Republic of Venice commissioned the simultaneous building of thirty wells in public squares and courtyards plus fifty-five in 1768.

Unfortunately, by the middle of the nineteenth century, many wells were buried and the puteals were sold to foreigners, antique dealers, private collectors and museums.

In 1882-84, the public water main was built and pipes were installed. Thus, wells began to fall into disuse and since then puteals were simply seen as decorative and artistic resources.

In some of the remaining puteals you can still read: "Commodiati Publicae Nec Non Urbis Ornamento ", which means at people’s service and decoration of the city at the same time.

Venetian wells are now around 600 and they are no more in use.